By Mike McGee

“We don’t inquire nearly enough what it means that the capacity for science itself exists in conjunction with our bodily makeup…. Our bodies are our primary instruments.” Michelle Kathryn McGee, October 24, 2017.

This very accurate assertion – that our most detailed and accurate science is capacitated through the body – is broad and wide-ranging. Due to a recent experience I’m going to ask questions about how the rest of our body affects what we see with our eyes. Since I am not a scientist, these questions, often beginning with known scientific fact, are an exercise in imagination, for your entertainment. The ultimate question, though: does what we see with our eyes represent what’s out there, or is what we see a modified version of what’s out there?

What do our eyes perceive? What other than light may be transmitted into the eyes and through the body to the visual cortex of the brain, where our visual images are formed? My hypothesis is that the images we see from the visual cortex of the brain may be composed of much more input, from different parts of the body, than simple pure light entering the eyeballs.

The corollary is that what we see projected on our brain may not be identical to what’s actually out there on the ground or in the air. We see the same things as others because mostly all brains are built to the same specifications. The entertainment for the use of your own imagination on is: do we really have any idea what’s out there beyond our bodies from a visual perspective?

I had glaucoma surgery last year. My whole body was physically affected for days by the very small, almost microscopic, incisions on my eyeballs. This experience caused me to speculate wildly about whether the eyeball is maybe more widely connected throughout the body than we realize.

I asked my very experienced glaucoma surgeon if other inputs besides light could affect what we see with our eyeballs, and she said absolutely not. The only input for vision is light. As a highly trained scientist, what she says is true. But only for our eyeballs….

I’ve done some amateur research, though, from scientific sources. For example, it is scientifically true that incoming light itself, received by the eyes, does not ever leave the eyeballs, much less reach the visual cortex of the brain. At the back of the eyeball this light is converted entirely into electrical impulses. The incoming light, then, ceases to exist. Do the newly generated electrical impulses transmit an exact replica of the incoming light? It’s hard to know, and right now unproveable.

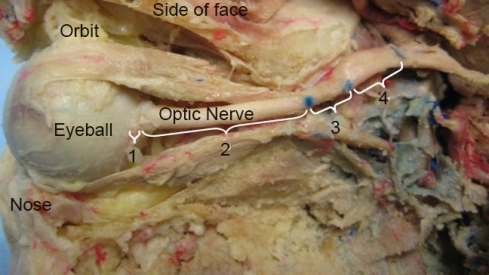

When this light strikes the rods and the cones inside the eyeball, these structures are excited with an electrical action potential. This excited electrical potential is passed to the optic nerve. The optic nerve can only transmit electrical signals. There is no light in the optic nerve. None. So, already what is sent on toward the visual cortex of the brain is something entirely other than the light coming in from the outside. This is a scientific fact, not subject to dispute.

It’s also a scientific fact that the optic nerve is covered with a series of sheaths (collectively: “myelin sheath”), somewhat like the insulation on a normal electrical wire. There is very little scientific discussion as to whether this sheath prevents outside inputs from the body from entering the optic nerve as it progresses on its long pathway from the eyeball at the front of the head to the visual cortex of the brain near the back of the head. There appears to be at best an assumption that this sheath keeps outside inputs at bay.

All along the length of the optic nerve, are breaks in the myelin sheath called the Nodes of Ranvier. At these points there is a means, called a sodium channel, and another a potassium channel, where there is physical input from the surrounding tissue into the optic nerve. We do not know how if at all these inputs affect the electrical signal.

Going back to our original premise, light from outside strikes an eyeball. We have only a very primitive understanding of how this incoming light, is altered by other parts of the visual system after being converted to electricity. Eyeballs, optic nerves, visual cortex. Each is a physical bodily structure. What we see must travel through our physical body before we can see anything.

Further, after light is converted into an electrical action potential at the back of the eyeball, there surely must be many influences from other physical bodily sources which may alter or reduce or augment the electrical current before an image is presented to our visual field for us to see. There may be inputs from vibrations, excess light, physical injury, the domains of fear and bliss, and other brain and bodily structures, which affect the images which are ultimately presented to our visual field for us to see.

In addition, there are other bodily influences besides the optic nerve which feed through different channels to the brain’s visual cortex to help in generating an image for us to see. We can be sure that the optic nerve is not the only neural pathway that feeds into the portion of the rear brain known as the visual cortex, which ultimately generates the images we see in our visual field.

After all, the brain is a somewhat amorphous mass, and to treat it like the wiring in a house is to grossly simplify what may be there. The visual cortex is an integral part of the whole brain, with many pathways and connections in and out.

As a simple example, normal facial recognition comes from a structure in the frontal cortex, far away from the visual cortex, which is in the rear of the brain. Yet each time we see a face, facial recognition kicks in instantly from the front of the brain as a signal to the distant visual cortex. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-we-save-face-mdash-researchers-crack-the-brains-facial-recognition-code/#

Another simple example is how we can see visual images even in the absence of light, such as in dreaming or in hallucinations, “The neural correlates of dreaming,” Nature Neuroscience, volume 20, pages 872–878 (2017). With dreaming, which is a normal activity, we can see that visual images of surprising complexity are regularly generated by our brain entirely without the presence of light. This very factual assertion leads to an imaginative question. Is it possible that these dream-type images are active when awake as well as when asleep, adding or obscuring what the light brings into the optic nerve?

Which brings us back to the final question. Since what we see with our eyes has so many components, do we really know what’s out there beyond our noses? Die Wahrheit ist irgendwo da draußen.

From http://www.mcgeepost.com Copyright © 2018 by Michael H. McGee. All commercial rights reserved. Non-commercial or news and commentary site re-use or re-posting is encouraged. Please feel free to share all or part, hopefully with attribution.

With respect to the final question, our visual system provides a filtered view of the world: limited sensitivity, limited angle of view, limited spectral response. It is, however, usually sufficient to prevent us from being eaten or run-over. There is an evolutionary pressure to select for sensory systems which map the external world faithfully.